Fault tolerance

Whether due to hardware failure, bugs, power outages, or even attacks: Individual nodes may fail at any time. The Internet Computer is designed to be fault tolerant, which means that the network will make progress even if some nodes fail or misbehave.

Handling node failures

In each round a block is proposed by the consensus layer and the messages in the block are processed subsequently by the execution layer. The proposed block and the resulting state need to be signed by at least 2/3rd of the nodes in the subnet in order for the subnet to make progress. As long as less than 1/3rd of the nodes in a subnet fail or misbehave, even in an arbitrary, Byzantine manner, the subnet will continue making progress.

Let us consider a scenario where less than 1/3rd of the nodes in a subnet fail while the remaining nodes of the subnet continue to make progress. We will now describe how a failed node can recover automatically and catch up with the other normally-operating nodes. A newly joined node also uses the same process to catch up with the existing nodes in the subnet.

Here’s one natural solution. A failed or newly joined node could download all the consensus blocks it missed from its peers, and process each block one by one. Unfortunately, new nodes will take a long time to catch up if they have to process all the blocks from subnet genesis. Another solution is to let the failed or newly joined node directly sync the latest state from its peers. However, the peers are continuously updating their state as they process new blocks. Syncing the latest state while the peers are updating it could lead to inconsistencies.

ICP follows a mix of both the approaches. The consensus protocol is divided into epochs. Each epoch comprises a few hundred consensus rounds. At the beginning of each epoch, all the nodes make a backup copy of their blockchain state, and create a catch-up package (CUP). The CUP at height h contains all relevant information required for consensus to resume from height h. This includes the hash of the blockchain state after processing the block at height h. The CUP is then signed by at least 2/3rd of the nodes in the subnet. Each normally-operating node then broadcasts the CUP.

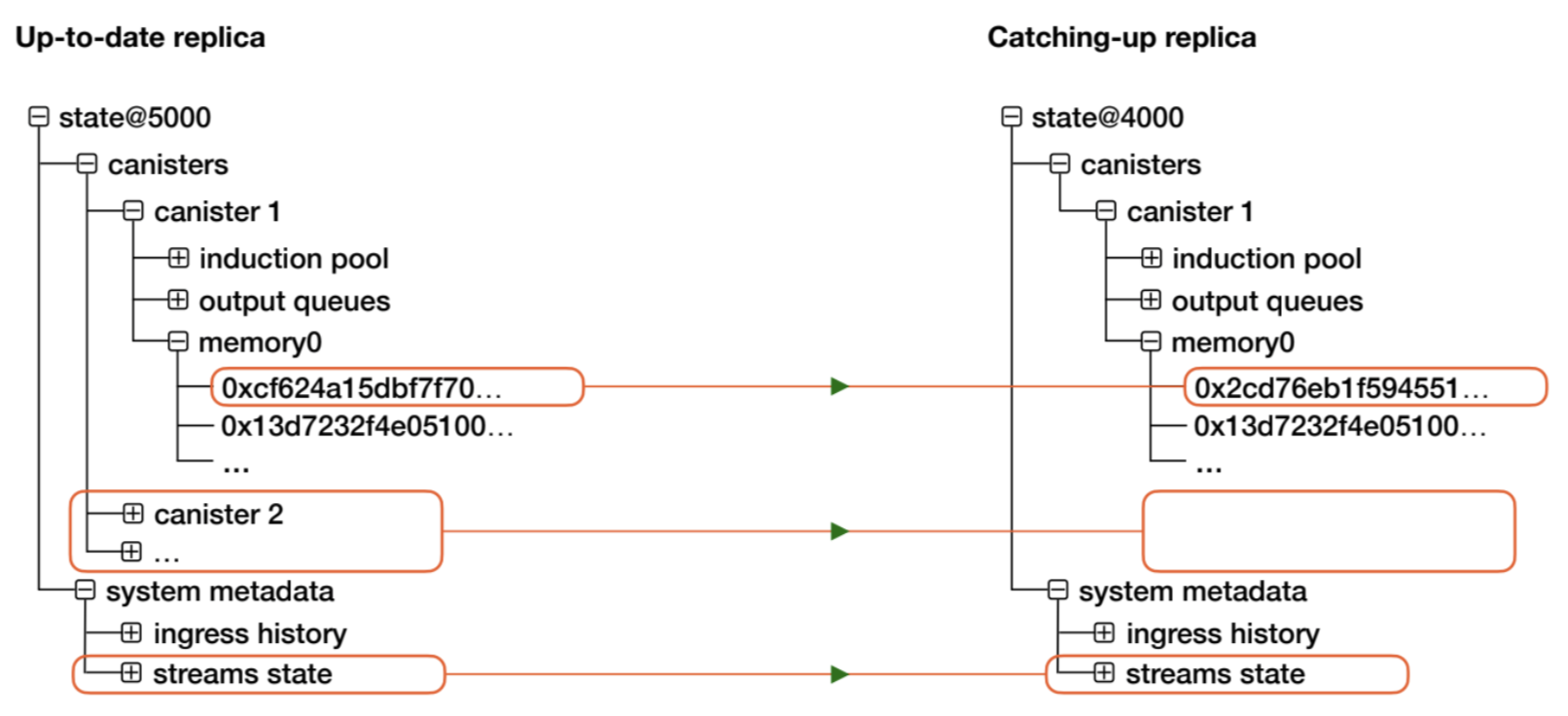

All the nodes in the subnet listen to the CUP messages broadcast by their peers. Suppose a node observes that a received CUP has a valid signature (signed by at least 2/3 of the nodes in the subnet) and has a different blockchain state hash than the locally available state hash. Then the node initiates the state sync protocol to sync the blockchain state at that height (the height at which the CUP is published). The blockchain state is organized as a Merkle tree and can currently reach a size of up to half a terabyte. The syncing node might already have most of the blockchain state and may not need to download everything. Therefore, the syncing node tries to download only the subtrees of the peers’ blockchain state that differ from its local state. The syncing node first requests for the children of the root of the blockchain state. The syncing node then recursively downloads the subtrees that differ from its local state.

Note that while the failed/newly joined nodes are syncing the blockchain state, the well-functioning nodes continue to process new blocks and make progress. The well-functioning nodes use their backup copy of the blockchain state (created at the same time as the CUP) to supply the state to syncing nodes. After the syncing node finishes syncing the blockchain state, it will request the consensus blocks generated since the CUP and process the blocks one by one. Once fully synced, the node can then process messages regularly like the other nodes.

Handling regular subnet failures

In rare cases, an entire subnet can get stuck and fail to make progress. A subnet can fail due to many reasons such as software bugs that lead to non-deterministic execution. This can also happen when more than 1/3rd of the nodes in the subnet fail at the same time. In this case, the well-functioning nodes fail to create and sign a catch-up package (CUP), and thereby the failed nodes cannot recover automatically.

When a subnet fails, manual intervention is needed for recovery. In a nutshell, as the subnet nodes fail to create and sign a CUP automatically, someone needs to manually create a CUP. The CUP needs to be created at the maximum blockchain height where the state is certified by at least 2/3rd of the nodes in the subnet. The subnet nodes naturally cannot trust a manually created CUP for security reasons. Therefore, we need a community consensus that the CUP is valid. The Internet Computer has a blockchain governance system called the Network Nervous System (NNS). We need to manually submit a proposal to the NNS to use the created CUP for the subnet. Anyone who staked their ICP can vote on the proposal. If a majority of the voters accept the proposal, the CUP is stored in the NNS registry.

Each node runs 2 processes — (1) Replica and (2) Orchestrator. The replica consists of the 4-layer software stack that maintains the blockchain. The orchestrator downloads and manages the replica software. The orchestrator regularly queries the NNS registry for any updates. If the orchestrator observes a new CUP in the registry, then the orchestrator restarts the replica process with the newly created CUP as input. As described earlier, the CUP at height h has information relevant to resume the consensus from height h. Once the replica starts, it will initiate a state sync protocol if it observes that the blockchain state hash in the CUP differs from the local state hash. Once the state is synced, it will resume processing consensus blocks.

Note that this recovery process requires submitting a proposal to the NNS, and therefore works only for recovering regular subnets (not the NNS subnet). This process of recovering a subnet is often termed as disaster recovery in many Internet Computer docs.

Handling NNS canister failures

The Internet Computer has a special subnet called the Network Nervous System (NNS) which hosts a lot of canisters that govern the entire Internet Computer. This includes the root canister, governance canister, ledger canister, registry canister, etc.

Suppose a canister in the NNS fails while the NNS subnet continues to make progress. This could be due to a software bug in the canister’s code. We then need to “upgrade” the canister, i.e., restart the canister with a new Web Assembly (WASM) code. Generally speaking, each canister in the Internet Computer has a (possibly empty) list of “controllers”. The controller has the right to upgrade the canister’s WASM code by sending a request to the subnet’s management canister. The lifeline canister is assigned as a controller for the root canister. The root canister is assigned as a controller for all the other NNS canisters. The root canister has a method to upgrade other NNS canisters (via calling the management canister). Similarly, the lifeline canister has a method to upgrade the root canister (via calling the management canister).

Suppose the governance canister is working. Then we can manually submit an NNS proposal to call the root/lifeline canister’s method to upgrade the failed canister. Anyone who staked ICP can vote on the proposal. If a majority of the voters accept, then the failed canister will be upgraded.

Handling NNS subnet failures

In the worst case, the entire NNS subnet could get stuck and fail to make progress. In such a case, all the node providers who contributed a node to the NNS subnet need to manually intervene, create a CUP and restart their node with the new CUP.